Csörgő-lyuk, Magyarország legnagyobb nemkarsztos barlangja

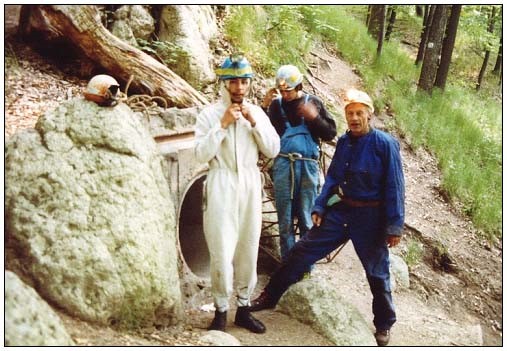

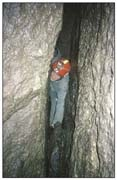

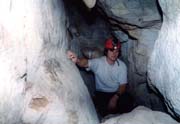

A barlang a Nyugati-Mátrában, Mátraszentimre határában, az Ágasvár-hegy déli lábánál található. Egyetlen bejárata vasrácsos ajtóval van zárva (kulcsát a Mátrai Tájvédelmi Körzet irodájában lehet igényelni). Ismertségének kezdete a múlt homályába vész, mely időkről csak töredékesen ismert legendák szólnak. Az első tudományos expedíciót 1869. május 17-én Szabó József, a híres geológus vezette az akkor 130 m körüli hosszúságú barlangba (SZABÓ 1871). A 19-20. század fordulójának éveiben a Magyarországi Kárpát Egyesület tagjai kutatták a barlangot, de az erről szóló feljegyzések eltűntek. Az 1950-es években végzett kutatásokról két tanulmány jelent meg (LEÉL-ŐSSY 1952, SZÉKELY 1953), de a további kéziratos jegyzőkönyveknek szintén nyoma veszett. 1982-től napjainkig folyamatosan végez feltárásokat a Csörgő-lyukban a salgótarjáni Sziklaorom Hegymászó és Barlangász Klub. Ezek nyomán közel 300 m- rel növekedett a barlang, mely így jelenleg 428 m hosszú és 29,6 m mély. A tudományos kutatásokat pedig 1990-től mindmáig az isztiméri Vulkánszpeleológiai Kollektíva tagjai végzik (ESZTERHÁS 1990, 2003). A barlang atektonikus képződésű labirintusrendszer, mert egy megbillent helyzetű, folyamatosan csúszó riodácittufa- (középső riolittufa- ) rétegben alakult. A kőzetcsuszamlásos barlangkeletkezést már Szabó József pontosan és plasztikusan megfogalmazta: “Az egész képlet helyzete és a barlangürnek általános iránya s alakja oda mutat, hogy a rétegek a nehézség törvényének engedve lassú, de folytonos csúszásban vannak a völgy mélye felé. Ezen tömegmozgás következtében a rétegek összetöredeztek s a darabok egymás fölött különböző sebességben mozogván, torlódások keletkeztek…” (SZABÓ 1871). A kőzettömbök délkelet felé csúsznak az átlagosan 20o-os lejtőn, így a feltorlódó kőtömbök között alakult üregrendszer folyosóinak többsége északkelet-délnyugati irányú csapásvonallal párhuzamos. A kőtömbök közti barlangjáratok mérete 7 a folyamatos csúszás miatt napjainkban is gyakran változik. A barlang bonyolult labirintusa több teremből és számos hosszabb- rövidebb folyosóból, valamint aknajáratból áll. A bejárásnál nehézséget jelent a szerteágazó járatok szövevényén túl, hogy a folyosók és aknák egy része igen szűk , valamint némely felül szűk akna lefelé hirtelen kitágul és több helyen omlásveszély is van. A barlangot ásványi képződmények nem díszítik.

A falakat, mennyezetet a világosszürke, szemcsés, néhol mállékony tufatömbök alkotják. Különösen látványos, névvel is illetett kőtömb a Nagy-teremben a szép formájú “Hajó orra” és az M-remdszerben a 8 m-es élhosszúságú “Szuper kocka”. A járószintek többségén is kisebb-nagyobb kövek vannak, az aprószemcsés törmelék kevés. A mélyzónában található az állandó vizű Vidróczki-forrás és egy időszakos tó a Denevér-teremben. A Meglepetés-terem falának néhány réséből állandóan erős vízcsobogás hangja hallatszik, de a vizet még nem sikerült elérni, meglátni. A Vulkánszpeleológiai Kollektíva tagjai vízfestéssel kimutatták a barlangi Vidróczki-forrás összefüggését a felszíni Vándor-forrással. A festett víz 7 óra alatt tette meg a 8 m szintkülönbségű, 130 m-es utat a két forrás között (ESZTERHÁS 1990). A barlang hőmérséklete hűvösebb, mint azt a külső klimatológiai tényezők indokolnák. A mélyzónában +4 oC körüli a nyári léghőmérséklet. Ezt a jelenséget a barlang töredezett és porózus kőzete által megnövekedett párolgási felület nagyobb hőelvonása magyarázza. A barlangban idáig 18 fajhoz tartozó állatok sokaságát sikerült meghatározni, melyek közül feltűnő a lepkék gyakorisága (Triphosa dubitata, Scoliopteryx libatrix, Inachis io) és különösen az Elveszett-ágban kis patkósdenevérek (Rhinolophus hipposiderros) több száz egyedet számláló áttelelő kolóniája (ESZTERHÁS 1990, 2003).

Néhány jellegzetes barlang bemutatása a különböző genotípusú más és más kőzetekben alakult üregek közül

A Mátra 87 ismert barlangja 3 kategória 14 genotípusába sorolható. E fejezetben minden egyes előforduló genotípus barlangjai közül példaként ismertetünk egyet (szingenetikus 2, posztgenetikus 11, mesterséges 1). Ércbánya 250 m-es szintjének ferde barlangja a gyöngyösoroszi egykori ércbánya által feltárt üregek közül a legnagyobb, melyet a forró oldatok a még teljesen meg nem szilárdult érces telér és a trachtandezit határán feszítettek. Nagyjából 12 m hosszú ferde hasadékszerű kristálykamra szélessége 2-3 m, magassága 4-5 m. Falait vastagon kérgrzték az oldatokból kivál, pirittel “megszórt” ametisztkristályok. A 8 barlang kristályait a felfedezést követően kirabolták, majd törmelékkel nagyobb részt feltöltötték. A bányászat felhagyása után (1989) az egész altárórendszert elárasztotta a víz (ESZTERHÁS 1996, ESZTERHÁS – GÖNCZÖL – SZARKA 1991).

Gyula-barlang a mátraszentimrei Csörgő-völgy jobb oldalának talpszintjén nyílik. Szája 7 m széles és 2,3 m magas, befelé egyetlen nagyobb fülke következik 3,6 m-es hosszal és 2,3 -2,7 m-es magassággal. Hozzávetőleg gömbnegyed formájú. Eredetileg teljesen gömb formájú gázhólyag lehetett kompakt andezitben, amelynek patak felőli részét a Csörgő-patak eróziója bontotta le és alsó részét ugyanezen patak törmeléke töltötte fel. A barlang kétszeri ásatása során számos cseréptöredék került elő, melyek a késő bronzkortól a középkoron át a napjainkig terjedő időkből származnak (ESZTERHÁS 1990, 1996).

Kék-útmenti-barlang a mátraszentimrei Ágasvár-hegy déli oldalában piroxénandezitben található tektonikus hasadékbarlang. Bejárata 60 cm széles és 2 m magas. A csak kúszva járható főfolyosója 3 m után egy keresztfolyosóba torkollik. A két hasadékfolyosó és néhány fülke alkotta barlang összhossza 9,7 m, legnagyobb magassága a folyosók kereszteződésében 2,5 m (ESZTERHÁS 1990, 1996).

Csörgő-lyuk riodácittufában alakult atektonikus barlang, melyet az előző fejezetben már részletesebben bemutattunk.

Herceg-gödri-barlang a parádsasvári víztárolóba folyó Herceg- gödri-patak mentén miocén eggenburgi homokkőben felszakadással alakult. A barlangot egyetlen 6 x 2 m-es alapterületű, 1,6 m magas fülke alkotja, melyet egy szűk bejáraton átpréselődve lehet elérni. A barlangtér morfológiai jegyei (pl. tölcsér formájú, laza homokból álló alja) azt mutatják, hogy az egy mélyebben levő üreg felszakadásával keletkezett, amit az is alátámaszt, hogy itt a homokkő mésztartalma eléri a 30 %-ot. Tehát a kőzet harmadrésze savas vízben oldódva üregesedett, mely a laza homokkőben felszakadást indukált.

Csák-kői Nagy-barlang a Gyöngyössolymos közvetlen szomszédságában levő, egykor riolit-malomköveket fejtő és készítő kőbánya csarnokából felszakadozásokkal részben konzekvenciabarlanggá alakult objektum.

Az üreg így végül is kettős genetikát tükröz. A déli része még őrzi a bányacsarnok formáját, tehát mesterséges üreg. Az északi, hosszabb labirintusrész viszont már az egykori bányacsarnok természetes felszakadozásával alakult konzekvenciabarlang. A barlang két részébe hat bejárat vezet. A csarnok és a labirintusrész együttes hossza 113 m, vertikális kiterjedése 14,5 m, horizontális kiterjedése 48 m (ESZTERHÁS 1996, ESZTERHÁS – GÖNCZÖL – SZARKA 1991).

Kis-kői-hasadék Abasár északi határában andezitből és andezitagglomerátumból felépülő szirten levő támaszkodó álbarlang. Egy szálbanálló sziklatömbről a közel függőleges irányú réteghatár mentén levált egy nagyobb kőzetkaréj, melynek alja megcsúszva eltávolodott eredeti helyéről, míg felső része nekitámaszkodott a helyben maradt részhez. Így egy hasadékhoz hasonló, 4,5 m hosszú, alján 60 cm széles, 2,2 m magas, a két végén nyitott barlangfolyosó alakult (ESZTERHÁS 1996, ESZTERHÁS – GÖNCZÖL – SZARKA 1991).

Csörgő-pataki-álbarlang a mátraszentimrei Csörgő-völgyben található tömbközi álbarlang (vagy táluszbarlang). A barlangot a völgyoldalról leguruló, egymásnak támaszkodó andezit-kőtömbök közti rések alkotják. A kőtömbök közti járható réseken a patak is átfolyik. Az álbarlang két egymással párhuzamos és egy az ezeket összekötő folyosóból áll, melynek összhossza 9,5 m, átlagos magassága 1 m. (ESZTERHÁS 1996).

Görgeteges-eresz a Domoszló melletti Tarjánka-szurdokban folyó patak oldalazó eróziója által kikoptatott barlang andezitagglomerátumban.

Mint az oldalazó erózió által alkotott üregeknél szokott lenni, az üreg szélessége meghaladja annak beöblösödését. Ez esetben 7,5 m a barlangeresz szélessége, 3 m-t tart befelé és átlagosan 1 m magas. Alján kisebb-nagyobb kőgörgetegek és andezithomok található. Árvizek esetén napjainkban is víz jár benne és a sodort törmelékkel tovább formálja a barlangot.

Macska-barlang a bátonyterenyei Macska-völgy szurdokszakaszában kőzetszéthúzódás által keletkezett barlang riodácittufában.

Macska-eresz időszakos vízesés alatt örvénylő erózió formálta üreg a bátonyterenyei Macska-völgy riodácittufájában. A 9 m magas vízesés alsó harmadában van a barlangeresz legmélyebb, 3,1 m-es beöblösödése. A vízesés falában még több mélyedés is van, valamint jól látszó vízszintes bordák képződtek az ellenállóbb rétegeknél a szelektív erózió hatására.

A völgy lemélyülésével a visszamaradó meredek völgyfal oldaltámasza megszűnt, így abban előbb feszültségek gyűltek össze, majd megrepedt és a repedés mentén a kőzettömbök barlangméretű rést hagyva eltávolodtak egymástól. A Macska-barlang teljes hossza 14,5 m, szélessége 1 m, magassága a legtöbb helyen 2 m körüli. Cserepes-eresz többnyire hő- és nedvességingadozás okozta aprózódással keletkezett üreg a parádi Cserepes-tető andezit- agglomerátumból álló meredek oldalának egyik sziklaszirtjében. A barlangeresz beöblösödése 3 m, szélessége 4,5 m, magassága a bejáratnál 4 m, beljebb 1 m. A leszakadt kisebb-nagyobb agglomerátumdarabok egy része legurult a meredek lejtőn, más része pedig az eresz alján halmozódott fel.

Mismucska-barlang a parádsasvári Köszörű-völgy alsó miocén kovás kötésű konglomerátmában lúgos oldódás által keletkezett barlang.

A barlang csőszerű folyosóit a kovás kötésű konglomerátumban csak a 9 pH-érték feletti lúgok voltok képesek kioldani. E lúgok a Köszörű-völgy feletti Gyökeres-tető ma már csak a gejzírkúpok romjai alapján felismerhető gejzírjeiből származtak. A gejzírekből előbb a felszínen, majd a kőzet repedéseiben alácsurgó lúgok számos csőszerű járhatatlan és barlangméretű folyosót oldottak a konglomerátumban.. Ezek egyike az elágazó folyosóhálózatot alkotó, 7,8 m hosszban bekúszható, 50-70 cm átmérőjű Mismucska-barlang Malomköves-csarnok a gyöngyössolymosi Csák-kő legnagyobb mesterséges ürege. A Csák-kő riolitjából egykor malomköveket készítettek. Ennek érdekében a legmegfelelőbb struktúrájú kőzetréteget követve bányacsarnokokat képeztek a riolitban. A malomköveket a helyszínen faragták ki a kőzetfalból, majd ácsolatba foglalva eresztették le a hegyoldalon.

A máig megmaradt legimpozánsabb bányacsarnok a Malomköves-csarnok. Bejárata 3 m széles és 1,8 m magas. Belső tere 19,5 m hosszú, 6-10 m széles és 1,8 – 3,3 m magas. A csarnokban ma is látható 9 rontott és így a falban hagyott malomkő (ESZTERHÁS – GÖNCZÖL – SZARKA 1991).

Esterhás István speleologus – Dr. Szentes György geologus

Csörgő Hole, the longest non-karstic cave in Hungary

The Csörgő Hole opens in the Western Mátra Mountains at the southern foot of Mount Ágasvár. Its only entrance has an iron gate. For many years the cave was forgotten about, and became the stuff of legends. The first scientific expedition to the cave was led by the geologist József Szabó on 17th May 1869. At that time the known length of the cave was 130 m (Szabó, 1871). At the turn of the XIX. and XX. century the Hungarian Carpathian Association carried out explorations, but the their report was lost. In the 1950‘s two studies were published on the cave (Leél-Őssy, 1952, Székely 1953), but unfortunately the relevant manuscripts disappeared. Since 1982 the members of the Climbing and Caving Club of the town of Salgótarján have been systematically exploring the cave. As a result of this the cave has recently been extended to 428 m long and 29.6 m deep. Since 1990 the Vulcanospeleological Collective of Isztimér has carried out scientific investigations in the cave (Eszterhás 1990, 2003).

The Csörgő Hole is an atectonic labyrinth. The development of the cave can be traced back to the continuous sliding of the rhyodacite tuff (Middle Rhyolite Tuff) and the consequent aggradation. The first explorer of the cave, the geologist József Szabó had defined exactly how the landslide had originated in the cave development: “The position of the surroundings and the direction of the passages indicates that the layers, obeying to the pull of gravity, are sliding slowly and continuously toward the bottom of the valley. As a result of this mass movement the layers are broken apart and boulders moving at different rates are piling up on one another….”. (Szabó, 1871).

The boulders are sliding south-eastwards on a 20o slope, therefore between the accumulated boulders passages have formed following a NE – SW strike. Because of the continuous sliding of the boulders, the size and form of the cavities are still frequently changing. The complicated labyrinth of the cave consists of several chambers, long and short passages and shafts. A tour in the cave is not easy due to the complexity of the passages , the narrow corridors and shafts as well as the danger of collapse . Speleothems are not to be found in the cave. The walls and the ceiling are formed of light grey, grained and partly weathered tuff boulders. The boulders in the Big Room are especially spectacular boulders as are those in the Prow and in the M System which contains the 8 m big Super Cube. The floors are covered with rock gravel and with some fine grained debris. In the deepest level of the cave the perennial Vidróczki Spring emerges and in the Bat Chamber an intermittent lake can sometimes be found. In Surprise Hall water can be heard gurgling through the fissures, but nobody has yet succeeded in reaching this underground stream. The members of the Vulcanospeleological Collective have proved by dye tracing the connection between the Vidroczki Spring and the Vándor Spring which emerges on the surface. The distance between the two springs is 130 m and the vertical difference is 8 m. The dye tested water emerged after 7 hours (Eszterhás 1990). The cave temperature is cooler than the surface temperature. The air temperature in summer is about +4 Co in the deep level. This phenomenon can be explained by the extensive evaporation area of the porous tuff, which results in greater heat extraction. In the cave 18 species have been identified. The large numbers of moths (Triphosa dubitata, Scoliopteryx libatrix, Inachis io) is unusual. In the Lost Passage large colonies of Lesser Horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposiderros) roost throughout the winter (Eszterhás 1990, 2003).

Description of some characteristic caves according to the types of cave development and the surrounding rock

The 87 caves of the Mátra Mountains are representing 14 types of cave developments in three main groups. In this chapter we describe examples from each types of the cave development (2 syngenetic originated caves, 11 postgenetic originated caves and 1 artificial cavity). The inclined cave at the 250 m level in the ore mine was a 12 m long, 2-3 wide and 4-5 m high sloping crystal cave. The cave was formed at the edge of an ore dyke and the tracyandesite which originated from the influence of the ascending hot solutions. Its walls were covered with large brilliant individual amethyst crystals and disseminated pyrite. Unfortunately, immediately after its discovery, the cave was looted and filled in. After the mining operations ceased (1989) the whole system was abandoned and flooded (Eszterhás1996, Eszterhás, Gönczöl, Szarka 1991).

The Gyula Cave opens on the base level on the righthand side of the Csörgő Valley. Its entrance is 7 m wide and 2.3 m high.

The cave consists of a single 3,5 m long and 2.3-2.7 m roundish niche, which was originally a completely ball-shaped gas bubble cavity in compact andesite. Part of the cave was denuded by the erosion of the Csörgő Creek and filled in by stream debris. The Gyula Cave is of archaeological importance. Excavations revealed potsherds dated from the late Bronze Age to the present days (Eszterhás 1990, 1996).

The Kék-útmenti Cave is a tectonic fissure cave, which was formed in pyroxene andesite on the southern slope of Mount Ágasvár. Its entrance is 0.6 m wide and 2 m high.

The first 3 m of the cave is a low crawl, which leads into a 2.5 m high fissure passage. The total length of the cave, including some small niches, is 9.7 m (Eszterhás 1990, 1996). The 428 m long Csörgő Hole, the longest non-karstic cave in Hungary, is atectonic cave in rhyodacite tuff. The Chapter 5 gives a detailed description of the cave.

The Herceg-gödri Cave is a collapsed cave in the Miocene Eggenburgian sandstone by the side of the Hereceg-gödri Creek. A narrow entrance opens into the cave, which has a single chamber measuring 6 x 2 m and is 1.6 m high. The morphology of the cave (for example the funnel shaped floor, which is composed of loose sand.) shows, that its development is the result of a breakdown in a deeper cavity. The lime content of the sandstone is 30%. A cavity developed because a third of the volume of the sandstone dissolved in the acidic water, which induced a breakdown in the loose sandstone.

Csák-kői Big Cave can be found in a former millstone quarry near the village of Gyöngyössolymos. It consists of a large cavity in rhyolite, caused by breakdown and thus is a consequence cave. There are two distinct parts to this cave.

The southern part is the original quarried chamber and consequently this is an artificial cavity. On the other hand the northern part, a long labyrinth has resulted from natural breakdown and has developed as a natural cave. There are six entrances to the artificial cavity and the natural cave. The length of both parts is 113 m with a vertical differential of 14.5 m and a 48 m horizontal extension. (Eszterhás 1996, Eszterhás, Gönczöl, Szarka 1991).

Kis-kői Fissure Cave is a leaning pseudocave. The cave opens in a cliff composed of andesite and andesite agglomerate north of the village of Abasár. There is a large cavity, formed in boulders along the horizontal bedding. The lower part of the boulders have slid and moved from their original position, while the upper part is balanced on bedrock. As a result of this a passage, 4.5 m long, 2.2. m high and 0.6 m wide, open at both ends, has developed. Csörgő-pataki Pseudocave can be found in the Csörgő Valley near the village of Mátraszentimre. It is a talus cave, a mass of fissures between the andesite boulders, which rolled down the valley. A stream flows through the open cavities in the valley. This pseudocave, which is 9.5 m long and an average of 1 m high, consists of two parallel passages, which are connected by a narrow fissure. (Eszterhás 1996).

The Görgeteges Rock Shelter was formed near the village of Domoszló in the andesite agglomerate of the Tarjánka Gorge by the lateral erosion of the stream. Generally the width of cavities formed by lateral erosion exceed their depth.

In this case the 1m high rock shelter is 7.5 m wide and is 3 m deep. The floor is covered with rock fragments and andesite sand. It sometimes floods and the water transported gravel is helping to extend the cave.

The Macska Rock Shelter is a cavity near the town of Bátonyterenye in the Macska Valley. The rock shelter was shaped by the evorsion in rhyodacite tuff below a waterfall. In the lower third of a 9 m high waterfall , there is a rock shelter with a depth of 3.1 m. In the rock wall several smaller hollows can be observed and spectacular horizontal tuff layers have formed due the selective erosion.

The Macska Cave can be found in the gorge of the Macska Valley. The cave was developed by rock extension in rhyodacite tuff. After the deepening of the gorge steep, backward sloping side had lost its lateral support and thus tension occurred in the rock mass. Later the rock cracked and the blocks separated from one another, forming a cave-sized fissure. The Macska Cave is 14.5 m long, 1 m wide and about 2 m high. Rock fragmentation, which was caused by the temperature and moisture variation, created the Cserepes Rock Shelter in a cliff on Mount Cserepes near the village of Parád. The rock shelter is found in andesite agglomerate. It is 4.5 m wide, 4-1 m high and is 3 m deep. Andesite agglomerate breakdown has accumulated on the floor.

The Mismucska Cave opens in Miocene siliceous conglomerate in the Köszörű Valley near the village of Parádsasvár.

The cave has formed as a result of the alkaline solution. Only a solution with a pH of over 9 would have been able to dissolve the passages in this cave The alkaline solution originated from the former geysers of Mount Gyökeres above the Köszörü Valley. Today the existence of these geysers can be identified only from the remains of the geyser cones. The seeping alkaline solutions from the former geysers dissolved several tube shaped cavities, both passable and impassable, in the conglomerate. One these is a the network of the 7.8 m long and 0.5-07 m diameter known as Mismucska Cave.

Malomköves Hall is the largest artificial cavity in the rhyolite of Mount Csák-kö near the village of Gyöngyössolymos. The rhyolite was originally used to produce millstones and as a result large cavities were cut in the rhyolite. The millstones were

carved on-site from the rock face and when finished, were mounted on timber sledges, and lowered down the hillside. The most spectacular underground quarry which can be seen today is the Malomköves Hall. The entrance is 3 m wide and 1.8 m high, and inside it is 19.5 m long, 6-10 m wide and 1.8-3.3 m high. In the left hand wall, nine half-completed, but damaged millstones can still be seen (Eszterhás, Gönczöl, Szarka 1991).

István Esterhás, speleologist – Dr. György Szentes, geologist